posted February 16 2010

having two eyes is vastly overrated

A few years ago I had to go to the RMV to get my driver’s license renewed. This involved, aside from the paperwork and general atmosphere of human degradation, a quick eye exam. In Boston this is done by peering into what looks like a table-mounted View Master, only instead of slides of the Superfriends, this one has an eye chart.

“Read the letters above the green line, please.”

“X-O-Q-T,” I say. This is followed by a slightly too-long pause.

“And the rest of the line, sir?”

“Oh,” I say, quickly recognizing the problem. I need to turn on my right eye. I squint my left eye shut to give my right eye a jumpstart, and the rest of the line pops into existence. “R-P-V-M.”

Without another word she moves on to the rest of the paperwork. I didn’t get my license renewed that day, but that’s a different story. The point of my telling you this is to let you know that like many people born with cerebral palsy, I have a lazy eye. Or rather, I had a lazy eye, surgically corrected when I was about two years old. As with language, where there’s a sensitive period during which the brain can soak up a native language with ease, there’s a similar period for the wiring of depth-sensitive neurons. This period occurs at a very early time in development, so my depth-sensitive neurons didn’t develop in an ideal manner.

I’ve spent most of my life with this crippling visual disability. Unable to play catch or aim a frisbee. Terrible at estimating how far away I am from anything. And most damningly, utterly unable to shake hands or open doors without accidentally punching someone in the mouth or mashing my fingers against the wall. My hands, they ache from being bitten and bludgeoned so.

Or, you know. Definitely not.

This is why articles like “How 3D Works (And Why It’s Back!)”, by Erez Ben-Ari, never fail to tick me off. They inevitably equate depth perception with stereopsis (literally “solid sight”), a phenomenon experienced when the two slightly different images hitting your eyes merge to produce a sensation of depth (this process is also called binocular fusion1). In reality, stereopsis is a minor contributor to depth perception, most useful within a range of five feet and essentially useless beyond twenty. The lion’s share of depth perception arises from monocular (one-eyed) cues. We tend to take these for granted since they seem so basic: the way solid objects overlap each other, the way things get smaller as they get farther away, changes in texture and other visible details, to say nothing of a little thing called motion, which always seems to get neglected in discussions of depth perception, academic or otherwise.

Mr. Ben-Ari’s article makes a mistake pretty early on when he claims that “3D imagery has been around for ages, mostly as a gimmick, but things have changed in the past few years.”

Well, sort of. Stereoscopy, or the process of creating a sensation of depth from a pair of 2D images, has been around since 1840. Sir Charles Wheatstone invented the first stereoscope (among a few dozen other things). In fact, Wheatstone’s stereoscope is still used in vision research today, as the apparatus is both cheap and easily adjustable for each observer. You can make one yourself, either with mirrors and cardboard or, if you’re feeling particularly American, with iPods. Even setting the research applications of stereoscopy aside, Ben-Ari’s claim that it’s mostly a “gimmick” is debatable. Any doctor who’s ever gazed into a professional-grade microscope will tell you how useful that extra depth cue can be. Of course, research into stereopsis eventually led Béla Julesz to the random dot stereogram, which in turn gave us the Magic Eye. That’s not just a gimmick, that’s torture. There is no Easter Bunny.

Ben-Ari can also be faulted for failing to do some basic research into the history of 3D movies. Discussing the various methods of projecting 3D movies he says, “…the most popular way, initially, was to use the notorious red-blue glasses…A few years ago, a new delivery method came about, based on polarizer glasses.”

Ben-Ari gives the impression that this polarization technique is all newfangled, arriving on the scene “a few years ago.” I suppose that’s true, if by “a few years,” you mean seventy-four. Polarized 3D movies were patented and marketed by the brilliant Edwin H. Land in 1936. In fact, he started a little Mom and Pop business called Polaroid, perhaps you’ve heard of it? Most of the 3D films shown during the “golden era” of 3D in the 1950s were projected using the polarized method, with the more well-remembered red-blue lens system being used for comic books and later TV adaptations.

All this is window dressing that hides Ben-Ari’s real whopper. After a discussion of the basics of binocular depth perception and before his inaccurate recounting of the history of 3D film, he casually says, “For this reason, people with a damaged eye cannot judge distances correctly.”

Oh, I beg to differ. So would cinematographers, surveyors, and snipers (and anyone who spends a lot of timing estimating distances with one eye shut, really), as well as Bryan Berad, the one-eyed professional hockey player. While we’re on the subject of sports, I found at least three Major League pitchers who are blind in one eye: Thomas Sunkel, who pitched for the Cardinals, the wonderfully named Whammy Douglas, who pitched for the Pirates, and Abe Alvarez, who pitched a few games for the Boston Red Sox during—get ready for it—the 2004 season.People with damaged eyes should be concerned more with their diminished field of view than anything else. Judging distances is not a problem.

Let it also be known that not all “damaged eyes” are equal. If you’re like me and you have some form of amblyopia then not all is lost. Evidence suggests that special visual exercises can restore an amblyope’s visual function to normal levels. At a large vision conference last year, I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Sue Barry, who showed me that I can even restore my stereopsis, provided I’m looking at the right things. My recent experiences at 3D movies like Up and Coraline have shown me that I am indeed capable of perceiving stereoscopic effects, which suggests that with training I might be able to fully restore my 3D vision.2

So let’s review. Erez Ben-Ari wrote an article on the resurgence of 3D movies in which he botches the science, rewrites history, and fundamentally misunderstands why this resurgence is taking place. It’s not really about improved stereoscopic technology (although it’s certainly easier today than it was in 1936, when two reels of film had to be meticulously synchronized to prevent the audience from dying of eye strain). It’s more about 3D as an attraction. You still can’t get good 3D in your home, which means that the theater is the place to be. For this reason, I doubt we’ll ever see a usable home solution for full-color 3D. If the movie industry hasn’t already gummed up the works on that project, they really should. It’s where the money is. Just look at Avatar.

-

By the way, binocular fusion’s evil twin is binocular rivalry, which occurs when the two images hitting your eyes are too dissimilar to be merged together. Rather than fusing them into a depth percept, your brain has a big argument over which picture you should be seeing, with your dominant eye (yes, just like you have a dominant hand, you have a dominant eye) usually winning out by default. This is why red-blue 3D glasses almost never work for me, and it’s also why I had that problem at the RMV. ↩

-

It really seems to depend on how much form information my brain has to work with. I’m hopeless on a random dot stereogram, where a perception of depth arises purely from binocular fusion, but as the object is more clearly defined (more realistic) and/or takes up more of my visual field, it gets easier to induce stereopsis. ↩

posted January 25 2010

first-person tetris

As games go, Tetris is hard to improve upon. Things like head-to-head play, “obstacle” Tetris, and 3D variations increase the novelty of the experience, but rarely make for a better game than the original 80s action puzzler. I had yet to see a modification of the original formula that actually makes for a better game, until now. Not only is this a pixel-perfect recreation of the classic Nintendo version, but it comes with a simple, brilliant twist that will make you laugh out loud, tear your hair out, and keep you coming back for more. I played Tetris—this exact version of it, no less—for hundreds of hours, and yet with this one simple change, the entire experience is fresh again. That’s quite an accomplishment.

posted January 19 2010

an acquired skill

From a recent article on video games, written by Charlie Brooker:

If you’re a gamer, you’ll naturally want others to share the experience. So you try to introduce the game to your flatmate, your girlfriend, your boyfriend. But they’re wary and intimidated. From their perspective, even the joypad is daunting. To you it’s as warm and familiar as a third hand. To them it’s the control panel for an alien helicopter.

But you persevere, press the pad into their unenthusiastic hands, and offer to talk them through a few minutes of play. And almost immediately you have to bite your tongue to avoid screaming. They run into walls or hit pause by mistake. They swing the camera around until they can see nothing but their own feet, then forward-roll under a lorry. They try to put the controller down, complaining that they’re “no good at this”. You force them to have another go, but within minutes you’re behaving like a bad backseat driver.

What’s funny is that not one week before I read this article, I had exactly this experience with Damian, he of the fine photography and frequent website comments. He was visiting Boston for New Year’s, and in one of our quieter hours I suggested he try out the demo for God of War III, which amounts to roughly fifteen minutes of truly exquisite violence. “I’ve never really played video games,” he said, by which I thought he meant, “I rarely play them, they are not my thing.” What he really meant was, “No, seriously, I’ve never played a video game. Certainly not one of these 3D ones.”1

Apparently his mother had forbidden him from playing such games as a kid, which strikes me as odd, as Damian routinely describes his mother as a garden variety California hippie, and not the sort of person I would imagine prohibiting a Playstation in the house. Well, you’re on the East Coast now, buddy, where the only rule is, there are no rules. Except that in Boston you can’t ride the subway after 12:30AM and in New Jersey you can’t make a left turn on a highway. Other than that, no rules.

Ever the good sport, Damian starts the demo and commences the surprisingly fun process of murdering several dozen faceless minions. The demo walks him through the basic controls as he plays. So far so good. Then we come to the Harpy Ride section. “Press L2 and Square to fire your bow,” says the game. Damian does so, thus attracting the attention of a nearby flying harpy the subtle way, by puncturing it with flaming arrows. As the harpy draws near, the game commands, “Press L1 and Circle to ride the harpy.” Again, Damian complies, and finds himself attached to the harpy as it flies across a small chasm, towards a second harpy he’ll have to commandeer if he wants to finish the crossing.

Here’s where we run into trouble. The game makes it simple to jump from one harpy to the other. As the player gets within range of the second harpy, the harpy is highlighted in a blue light. Press X, and the player will simply jump onto the highlighted harpy. The thing is, the second harpy never lights up. Damian seems to get close to it each time, and maybe it flashes blue for a split second, but never long enough for him to press X and grab on. This section of the demo takes a little getting used to, and most people mess it up once or twice. But six times? Seven? Troubling.

Finally, I see the problem. God of War uses a fixed-camera system, allowing the game designers to present each section of the game as beautifully and cinematically as possible. During this particular section the camera is at a 30-45° angle to the action. Instead of moving in a straight line over the chasm, Damian is veering sharply to the right.

“You’re moving him off to the right. You need to move him more forward.”

“I am.” Welcome to the joys of backseat video gaming, by the way.

“No you’re not. Move him away from the camera.”

“And which direction is that, Jon?”

“You know, forwards…away…in. Move him into the screen.”

At this point I get up and move myself behind Damian so that I can look at the controller. I look at the control stick and imagine myself playing this section of the demo. “Up and just a bit left.”

And just like that, he was across.

I find it downright fascinating that Damian had a problem here, because for any experienced gamer there is simply no problem to be had. The game tells me to move, and I just know how to do that. The fact that I’m using a 2D control stick to move in 3D space doesn’t even register, because I first learned how to do this kind of spatial conversion, what, fifteen years ago? I don’t even know which game might have been responsible for rewiring that part of my brain. Final Fantasy VII? Battle Arena Toshinden? Super Mario RPG? Q*bert? God only knows.

The point is, this sort of spatial mapping is an acquired skill, one I learned entirely through video games. It’s easy to think of more specific examples. Are there four unlit torches in an otherwise empty room? Is this a Zelda game? Well then, let me go get my matches. I once played Zelda: The Wind Waker as my brother, nine years younger than me, observed the action. I was visiting home from college, and this was thoroughly His Game. I walked into the dungeon, saw the unlit torches, and, without a second thought, proceeded to light them. “How did you know how to do that,” he asked, confident that his older brother would’ve gotten stuck on this puzzle, crying out for assistance. I said, “I have been lighting these torches since before you were born.”

Light the torches. Move the stick up and to the left to go in. Who says video games can’t teach you anything?

-

I’m paraphrasing the conversation. Damian could probably fill you in on the exact sentences. His memory is truly prodigious. ↩

posted January 11 2010

child's play 2009: conclusion

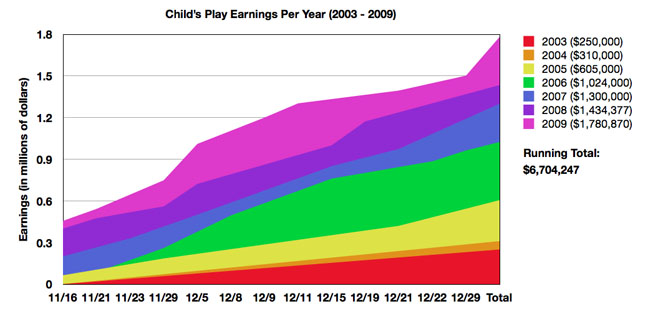

Child’s Play 2009 has concluded, or rather, the Holiday Season fundraising period has concluded. The charity is maintained year round, so if you’d like to donate, you can still do so. The tally for the roughly two month long fundraising period comes to $1,780,870 (click the chart above to enlarge). Funny, that final tally sounds familiar:

Child’s Play 2009 has concluded, or rather, the Holiday Season fundraising period has concluded. The charity is maintained year round, so if you’d like to donate, you can still do so. The tally for the roughly two month long fundraising period comes to $1,780,870 (click the chart above to enlarge). Funny, that final tally sounds familiar:

Could Child’s Play break two million dollars this year? Actually yes, but only under a fairly optimistic interpretation of the data…I wouldn’t be surprised to see Child’s Play hit 1.7 million dollars this year.

The funny thing is that I had originally wanted to put down my estimate at 1.8 million dollars, but I second-guessed myself, reasoning that this number was too close to the oh-so dreamy two million dollar mark. Again, the generosity of the gamer community amazes me. So, too, does the sudden spike in cumulative funds right at the end of the drive. This hasn’t happen in any previous year, and I’m wondering if it’s the result of a surge of last-minute donors, or something more mundane, like a quirk of the charity’s bookkeeping. In any event, I’m fairly confident that next year’s charity will raise a positively shocking two million bucks. I can hardly wait.

While we’re on the subject, you also might want to check out the latest episode of Penny Arcade: The Series, which is part one of a two-part feature on Child’s Play.

posted December 1 2009

a small thanksgiving miracle

Nothing says Thanksgiving quite like swine flu, am I right, folks?

Yes, it’s true. The Tall One and I came down with The Flu That Dare Not Speak Its Name within days of each other. The Tall One got a blood test to confirm it, and since I was vaccinated for the less glamorous seasonal influenza, I’m assuming that my flu-like symptoms have been the product of the more exotic variety. The only odd thing was my lack of fever, but apparently a lack of fever is an unusually common feature of swine flu. The aches, chills, fatigue, and absolute bastard of a cough all scream “FLU!” to me, so I think I’ll be skipping the University’s much-delayed H1N1 clinics, if they ever happen.

H1N1 is not smallpox, no matter what CNN says. Owing to its bits and pieces of porcine RNA, most immune systems will get hit a little harder by this flu, but unless you have a suppressed immune system or a pre-existing pulmonary condition, you can shelve any nightmare scenarios you might have had about drowning in your own lungs. This flu will, however, knock you out of commission for about a week.

Did I mention that the week we got the flu also happened to be the week of Thanksgiving? This killed the plans we had to interface with healthy humans (I, keeping it local with friends, the Tall One, visiting family). Instead of seeing our loved ones, we would cough angrily into the void. Instead of chowing down on turkey and its various and sundry accent foods, we would quietly shiver in the living room. The only upshot to the flu is the appetite suppression, which would make it easier to bear the thought of all that food we wouldn’t be eating. Like pumpkin pie. Oh sweet God, THE PUMPKIN PIE!

And then! Riding in on a horse named Thanksgiving Miracle came the Tall One’s father, a man who on this website shall be referred to as (the incredibly story-appropriate) Papa Tasty. When Papa Tasty first heard of our illnesses he resolved to visit us on Thanksgiving and “bring some food”. I had expected a pumpkin pie and maybe some McNuggets. Let it be known that Papa Tasty, who is of Italian descent, does not screw around when it comes to food. He brought with him a Mayflower’s worth of goods: a fresh turkey, to be cooked according to tradition, mashed potatoes, stuffing, meatloaf, homemade chicken soups, plural, pumpkin pies, plural, shaved Asiago cheese, two kinds of cheese spread, bagel chips for appetizers, and a pre-cooked rotisserie chicken that existed solely to be eaten while the turkey cooked. When I expressed shock and disbelief at all this, he looked at me as if to say, “It’s Thanksgiving. You expect me to do this any other way?”

And then! Riding in on a horse named Thanksgiving Miracle came the Tall One’s father, a man who on this website shall be referred to as (the incredibly story-appropriate) Papa Tasty. When Papa Tasty first heard of our illnesses he resolved to visit us on Thanksgiving and “bring some food”. I had expected a pumpkin pie and maybe some McNuggets. Let it be known that Papa Tasty, who is of Italian descent, does not screw around when it comes to food. He brought with him a Mayflower’s worth of goods: a fresh turkey, to be cooked according to tradition, mashed potatoes, stuffing, meatloaf, homemade chicken soups, plural, pumpkin pies, plural, shaved Asiago cheese, two kinds of cheese spread, bagel chips for appetizers, and a pre-cooked rotisserie chicken that existed solely to be eaten while the turkey cooked. When I expressed shock and disbelief at all this, he looked at me as if to say, “It’s Thanksgiving. You expect me to do this any other way?”

Were we ill with flu? YES. But was it all delicious? YES. Did I slip into a food coma? YES. Do we have more leftovers than we know what to do with? YES. Was it a Thanksgiving? YES.

So let it be known that on this Thanksgiving, though I had many things to be thankful for, I was above all thankful for the company, kindness, and generosity of Papa Tasty, who went out of his way to make sure that two sick dudes in Boston did not go without a proper Thanksgiving.

posted July 20 2009

the man who knew too much

Alan Turing is the most important and influential scientist you’ve never heard of. You’ve perhaps heard the term “Turing test” come up in discussions of artificial intelligence, but this represents a minuscule slice of the man’s work, and an often misremembered one at that. At the start of his career, Turing answered what was thought by many to be an unanswerable question in pure mathematics. To solve the problem, Turing took an imaginative leap that, incidentally, invented the modern computer. During World War II, Turing was the mastermind behind England’s incredible efforts to crack the German Enigma code, and in this capacity probably shortened the length of the war by several years. It was only in his post-war career that he became interested in artificial intelligence (probably the natural evolution of his interest in symbolic logic, which lies at the heart of the answer to the aforementioned formerly-unanswerable question).

What most people don’t know about Turing, even many of the academics who speak of him as the Founding Father of This or That in the chiseled-in-stone intonation reserved for Darwin, Newton, Einstein, and Obi-wan Kenobi, is that he was gay. Once the British government learned of his homosexuality, at the time illegal in Britain, they put him on a regimen of psychoanalysis and estrogen injections. Unsurprisingly, Turing killed himself shortly thereafter by biting into a cyanide-laced apple. If the reader is interested, Wikipedia, as always, has more.

I learned most of these things by reading David Leavitt’s The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer. I had wanted to learn more about Turing as a man instead of a collection of ideas, but the tone of the book is far more academic than I had anticipated, with Leavitt walking us through the often highly technical highlights of Turing’s brilliant work. This book is part of a “Great Discoveries” series, and I suppose it’s my own fault for expecting the wrong things out of it. In my defense, Leavitt’s prologue chapter makes it seem like the emphasis is going to be on the personal. His thesis, if a biography can have such a thing, is that Turing’s work in artificial intelligence was deeply connected to his homosexuality.

Unfortunately, Leavitt’s case for this connection is thoroughly unconvincing. He relies mostly on pop-psychological speculation and comically strained analogies. For example, “As a homosexual, he [Turing] was used to leading a double life; now the closeted engineer in him began to clamor for attention…”

This is particularly hilarious in light of the previous chapter, where Leavitt makes it clear that far from leading a “double life,” Turing was surprisingly honest and nonchalant about his sexuality, seeing it as a non-issue (a daring and even dangerous stance for a man of his time). Leavitt claims that Turing’s homosexuality made him an outsider who was “disinclined to overidentify with larger collectives,” thus giving him the sort of unconventional perspective that allowed him to solve a major mathematical quandary and invent the computer as a byproduct of his thought process. Later in life, as Turing is defending the potential of thinking machines, Leavitt makes a tortured jump and posits that Turing was secretly boosting not for the rights of machines, but for gays.

Leavitt is simply wrong about the influence of Turing’s homosexuality on his academic pursuits. The connection isn’t there, no matter how badly Leavitt would like this to be the case. I’d like to offer an alternative I find much more interesting.

Were Turing growing up today he would definitely be diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Let’s be clear. I loathe autism’s status as the defacto pediatric diagnosis of the 2000s. Autism diagnoses increased ten fold between 1994 and 2006, and if you’re going to blame it on anything but hypochondria and over-labeling, the burden of proof is officially on you. Still, Alan Turing was a textbook case. As a mathematician, he lived almost entirely in his own head, had a variety of well-documented obsessive-compulsive behaviors, was famously literal-minded (if you used a metaphor around him, he’d take it at face value), and, most importantly, seemed to have little to no concept of social interaction. It’s not that Turing was shy or weird. He fundamentally did not understand how to interact with people in a social context. Like other high-functioning autistics such as Temple Grandin, social subtleties, the little nods and winks that we take for granted every day, went clear over his head. His total lack of social skill made him lonely and greatly hampered what could have been an even more stupendous intellectual career.

This, I believe, is the essence of Turing’s interest in artificial intelligence. The famous Turing test is straightforward. Put a human behind Door Number One. Put a computer behind Door Number Two. An observer in a third room types questions, and the human and computer type their answers back. How do we know that our computer is capable of true artificial intelligence? If it can fool the observer into mis-identifying where the computer is. Turing, in essence, defined a thinking machine as one that was able to engage itself in very accurate social cognition.This makes perfect sense in light of the way Turing lived his life. His mental world was one of pure logic. Out in the real world, he was unable to handle the complexities of social interaction. How perfect, then, that he would try to create a machine that could operate perfectly in the social sphere using pure logic as its foundation. In my opinion, the line from Turing’s mind to Turing’s machine is all too clear.

Turing’s hopes for thinking machines were overambitious, and scientists now tend to focus on building computational models and machines that simulate smaller slices of intelligence, rather than trying to create some kind of domain-general machine that can think just like a human (as the latter has proven to be incredibly difficult). In the realm of social cognition, progress has been cute but somewhat misleading. Attempts to simulate social cognition are only successful when you define “social” very, very narrowly, and it’s a fairly safe bet that Turing would be dismayed with the state of the art.

Turing’s real legacy may be a more philosophical one. In the 1950s he routinely defended the notion of thinking machines against all sorts of religious, artistic, and emotional attacks. His arguments were notable for their elegance and foresight. When confronted with a criticism such as, “A machine will never be able to compose a sonnet or paint a beautiful picture!” Turing might answer, “Well, neither can I, but surely you’d agree that I am still capable of thought?” He even dared to imagine that intelligent machines might prefer to converse among themselves, as so much of human convention would be irrelevant to them. Perhaps most importantly, he emphasized that in order for a machine to be considered intelligent, it cannot be infallible. This idea, unprecedented at the time, prefigures all modern work in computational neuroscience. If I’m building a learning algorithm, I don’t want a machine that simply gets better and better as I feed it new input. I want a machine that has not only human-like successes, but also has human-like failures.

Turing’s homosexuality did not influence his work. Being gay was a non-issue for him (although unfortunately, it was very much an issue for the British government). Turing’s real motivation comes from his desire to take his greatest strength—logic—and use it to unlock the secrets of social interaction, his greatest weakness. Although Turing’s goal remains elusive, he is one of the most influential thinkers in the history of artificial intelligence research. His philosophy lives on not just in science, but in Spock, Data, and the work of anyone else who ever wondered what it would be like if computers could think.